Lifespan is one of the very, very few books that can be life-changing.

It is a report on the exciting developments in eliminating—and reversing—aging. And it’s written by one of the pioneers in the field, David Sinclair of Harvard and MIT.

Sinclair’s credentials are staggering. Here’s just part of them, from the book’s end matter:

a tenured professor of genetics, Blavatnik Institute, Harvard Medical School; co-director of the Paul F. Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging Research at Harvard; co-joint professor and head of the Aging Labs at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia; and an honorary professor at the University of Sydney. . . . He has published more than 170 scientific papers, is a coinventor on more than 50 patents, and has cofounded 14 biotechnology companies in the areas of aging, vaccines, diabetes, fertility, cancer, and biodefense.

This book was written in 2019, so it is fairly up to date. Its message is: age-reversal and hundreds of years added on to your lifespan is coming, it’s unstoppable, and it will be here soon.

Although he doesn’t stress it, the barriers are political not scientific or technological. Every nation in the world has an FDA-type government body devoted to stopping medical progress. As I understand it, in no country on earth can a researcher even inject himself with his own creation.

But there are loopholes and ways through the briar patch of controls. One such is to get an age-fighting or age-reversing substance approved as a treatment for one particular disease, say diabetes, and then use it “off label” as a general remedy.

Sinclair’s conclusion:

It’s also hard to know what I know, to see what I’ve seen—the results of experiments and other clinical trials around the world years before the rest of the world learns about them—and not believe that something profound is about to happen to humanity.

The value of this book is its evidence that we will get young again and its explanation of how and why. You’ll learn about “longevity genes,” animals that already live centuries, why aging is a (curable) disease not “just man’s fate,” the role of the “epigenome,” vigor-enhancing lifestyle changes you can make now, and good food supplements to take now (nothing weird).

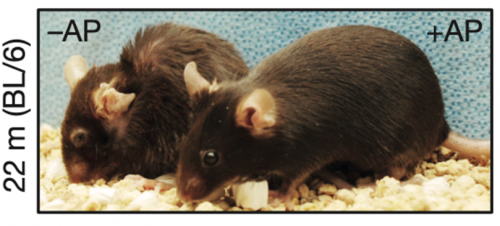

I know you’re still skeptical, to put it mildly. So here is visual evidence:

The mice, as I understand it, are the same chronological age, but look how much younger the one on the right looks. Compare the hair on their backs, and their eyes.

I’m not sure if this particular mouse had looked older (like the one on the right) and then was de-aged, or it just has aged much more slowly. That’s an important distinction for some of us who are already the mouse on the left. But other studies with other treatments have shown mice de-aging.

Mice are mammals, like us. They are actually very good representatives of human biochemistry and physiology. And we’re talking about something fundamental, something having to do with how DNA works, not anything pertaining to how mice differ from men.

That picture is not from the book, but here’s a passage that is:

“David, we’ve got a problem,” a postdoctoral researcher name Michael Bonkowski told me one morning in the fall of 2017 when I arrived at the lab. . . . “The mice,” Bonkowski said, “They won’t stop running.”

The mice he was talking about were 20 months old. That’s roughly the equivalent of a 65-year-old human. We had been feeding them a molecule to boost the levels of NAD, which we believed would increase the activity of sirtuins. If the mice were developing a running addiction that would be a very good sign.

“But how can that be a problem?” I said. “That’s great news!”

“Well,” he said, “it would be if not for the fact that they’ve broken our treadmill.”

As it turned out, the treadmill tracking program had been set up to record a mouse running for only up to three kilometers. Once the old mice got to that point, the treadmill shut down. “We’re going to have to start the experiment again, Bonkowski said.

It took a few moments for that to sink in.

A thousand meters is a good, long run for a mouse. Two thousand meters—five times around a standard running track—would be a substantial run for a young mouse. . . . Yet these elderly mice were running ultramarathons.

The book has 50 pages of footnotes. I would skip Part III entirely—it’s on social political implications and he brings in his own political ideology, which is badly mixed (to put it optimistically).

There’s a co-writer, who’s a journalist and writer, not a scientist. The result is a very readable book.